Version control with Git

by Christoph Buchner (bilderbuchi)

In this chapter, you will learn about version control and why you should use it. You will get a short introduction to Git, the version control system of choice for openFrameworks. The major concepts and keywords are explained, enabling you to easily dig deeper into the subject using available online resources. A number of tools for working with Git are presented. You will learn about Github, a web service for hosting Git repositories and one of the major platforms for "social coding". You will be shown how you can start hosting your own projects on Github and leverage its features. Finally, you will learn how you can build upon the things you just learned and where you can get help if you get stuck.

What is version control, and why should you use it?

How do you track the state of your projects over time? Have you ever made several copies of your project folder (or text document, Photoshop file,...)? Did you name them something like Awesome_project_1, Awesome_project_may10, Awesome_project_final, Awesome_project_final2, Awesome_project_really_final,...? Did you mail around zipped projects to collaborators, and had some trouble synchronizing the changes they (or you) made in the meantime? Have you run into problems when you had to go back to a previous version, change things, copy those changes to other version, or generally keep tabs on changes?

If you nodded at some of these questions, you've come to the right place - version control is there to help you! Version control (also called revision control) is the management of changes to documents, computer programs, large web sites, and other collections of information. It is used to easily, efficiently and reproducibly track changes to all kinds of information (like a really advanced "undo" function). Specifically, in programming it is (primarily) used to track changes to your source code, but it's generally applicable to most kinds of files on your computer. Version control also enables programmers to effectively collaborate in teams, because it offers methods to distribute changes, merge different development versions together, resolve conflicts if two (or more) programmers modified the same file, sync state between computers, etc.

I hope you'll agree by now that it is a very good idea to use some manner of version control when developing your programs. In the next section, I'll talk a bit about the different choices you have when choosing a particular system.

Different version control systems

There is a number of version control systems out there, some of which you've maybe encountered already. They can be divided into two big camps: "centralized" and "distributed" systems.

In centralized version control systems, a central server orchestrates the various tasks the version control system performs, and programmers synchronize with this server. Common operations often need a network connection to the central server. Typically, programmers only have a part of the whole project locally available. Some popular centralized version control systems are:

- Concurrent Versions System (CVS), which has introduced the "branching" concept into version control systems.

- Subversion (SVN), a popular successor to CVS.

Distributed version control systems, on the other hand, take a peer-to-peer approach. There is no central server, and every (local) repository contains all files and history (thus acting as a backup, too!). Network access is only needed for syncing changes with other programmers. Distributed version control systems have recently gained much popularity. Some notable systems are:

- Git was initially designed and developed by Linus Torvalds for Linux kernel development. Its popularity has recently boomed.

- Bazaar is a distributed version control system created by Canonical (the company behind Ubuntu). It is primarily used on Launchpad, a code hosting platform primarily used for developing projects around Ubuntu.

- Mercurial was started around the same time as Git. It is quite similar to Git, especially to a newcomer.

Introduction to Git

openFrameworks uses Git to version-control the code base, and relies on Github as a hosting platform for the code and the issue tracker. In this section, I'll give you an introduction on how to use version control with your openFrameworks project, and introduce the relevant concepts and commands as they are encountered.

Note that this chapter is only an introduction, and as such only touches the surface of Git's capabilities, both in the presented commands, and their options. Much more detailed information, including in-depth tutorials and a command reference, can be found online. Some links are collected at the end of the chapter, and most commands presented have a link to their online reference.

In what follows, I'll explain the basic concepts of Git. After that, I'll show the typical operations involved in using Git with an openFrameworks project in a walk-through fashion. Then I will show you how to work with remote Git servers.

Basic concepts

When you put your project (which is contained in a directory on your disk) under version control, Git creates a repository in your project directory. This means that the contents of that folder are tracked with Git. Most of the files associated with Git are in the .git folder in your project root (the leading dot means this folder is by probably hidden from view in your file browser by default).

The basic element for tracking the history of the repository is the commit. This is basically a snapshot of the repository's state at the time of the commit, including a commit message and any parent commit(s). Think of it as a checkpoint for saving in a videogame. It has a unique identifier called the hash (or SHA). This is a checksum calculated from the commit's contents. It's impossible to change any part of the commit without the hash changing. Thus, a commit hash uniquely defines a commit and the whole history preceding it.

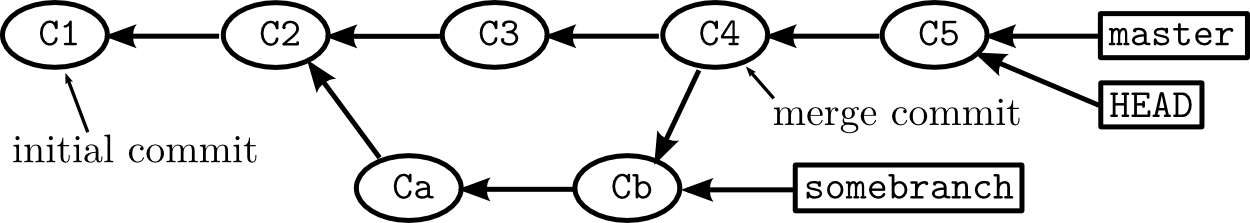

As your work proceeds, you will be adding commits, describing the things you change. These commits will form a chain of commits, making up the project history. A chain of such commits is called a branch, and the default branch is called master. Branches can also be created when you decide to diverge from a line of development, and try something different (for example a new feature, or a bug fix) while preserving the state of the project. This new chain of commits, which branches off at a certain commit of the original branch, now forms its own branch.

Branches can be merged into another branch. When this happens, Git analyzes the two different branches and merges their different histories/changes together.

This figure visualizes how this looks like:

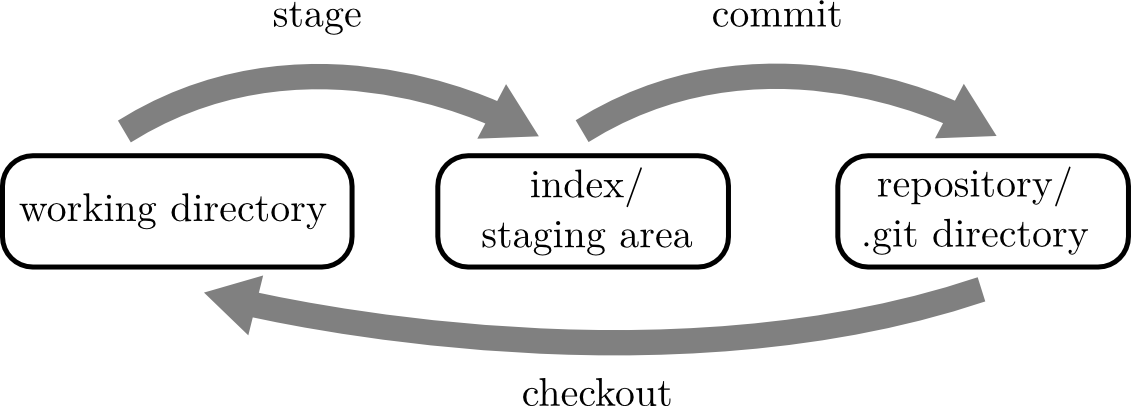

Finally, there are three different "areas" in Git, which you will encounter often when reading about Git:

The repository in the .git directory contains all the commits. The HEAD points to the current commit of the branch you are currently on. This represents the latest committed state of your repository. If you create a new commit, it will become this commit's parent (and HEAD will be moved to the new commit).

The working directory contains the files and folders under version control, the stuff you modify and work with when writing code for your project.

When you prepare a commit, you first have to stage any changes you want that commit to contain. This means that these changes will be put into the index (or staging area).

So, you modify your files in the working directory, you stage those modifications, putting them into the index, and then you create a commit, taking the files from the index and storing them in the repository. To get files back from the repository (i.e. restore the state as it was at some previous point), you check out files, putting them into the working directory. This is shown graphically in the following figure:

Armed with these basic facts, we can dive right in, and start working on our first project!

Getting started: project setup

You can follow along with this section by entering the given commands (in the line starting with $) into your terminal. You can also use a Git program with a GUI if you want (some will be presented later in the chapter), but you will have to figure out which actions correspond to the respective terminal commands.

Much of what follows will be less tedious to achieve, and presented in a prettier way, if you're using a GUI to interact with Git. Nevertheless, I am presenting this intro with a terminal-based approach for several reasons:

- I think it's actually more instructive to follow some typed commands than pages after pages of (rapidly outdated) screenshots of a GUI app you probably don't even use (as there are quite a lot of them out there).

- Many GUI programs don't offer the full range of functions that Git provides, so you will probably have to drop down into a terminal sooner or later. At that point it's quite handy to know what your GUI does in the background.

- Most of the online documentation and advice on Git focus on the command-line interface.

First, we have to set up Git itself for our operation system. This mainly involves downloading and installing and setting the username and email address. The instructions vary slightly depending on the operating system.

When we have successfully set up Git, we create a new, empty project with the OF project generator. We will end up with a project folder containing some C++ files and some IDE files depending on OS and chosen IDE (in my case: Linux and Code::Blocks). Note that Code::Blocks is no longer supported as an IDE for openFrameworks. This is left here just as an example. This will look similar to this:

$ tree -a --charset ascii

.

|-- addons.make

|-- bin

| `-- data

| `-- .gitkeep

|-- config.make

|-- demoProject.cbp

|-- demoProject.workspace

|-- Makefile

`-- src

|-- main.cpp

|-- ofApp.cpp

`-- ofApp.h

3 directories, 9 filesNow, it's time to create our Git repository, using the git init command:

$ git init

Initialised empty Git repository in /home/bilderbuchi/demoProject/.git/.gitignore

One thing we should do right at the beginning is add a special Git file called .gitignore to the root of our repository.

It's important that the Git repository contains all files necessary to successfully compile our program, but no unnecessary stuff. Generally, this means that files we edit by hand (e.g. source and header files, Readme files, images,...) should be included in the repository, but files which are generated from our code (e.g. compiled binaries, pdfs generated from some source file, video files or image sequences created with our program) should stay out. Also, user-specific files like IDE files describing the location of windows in our IDE, or backup copies of our files that the OS creates, don't really belong in the repository.

If we take care of this right at the beginning, we can easily make sure that only "proper" files end up in our repo. Git handles this file exclusion with the aforementioned .gitignore files (there can be several), which contains patterns describing which files are ignored by Git. Those ignored files will still exist in our working directory, that means we can still use them, but Git will not track them.

If, later down the line, we see files appearing in our list of changes which should not be there, or if we can't seem to add a file that belongs in the repository, we don't force Git to do what it doesn't want to, rather fine-tune the .gitignore pattern to match our expectations. Note that the .gitignore pattern does not affect files that have already been committed.

Because it can be daunting to come up with a generally useful .gitignore template, it's currently planned that the project generator will optionally add a pre-made .gitignore file when we create our project (the template can already be found at scripts/templates/gitignore/.gitignore). This file will look similar to this (formatted into three columns for convenience):

$ pr -tW84 -s"|" -i" "1 -3 .gitignore

###########################| |.externalToolBuilders

# ignore generated binaries|# XCode |

# but not the data folder |*.pbxuser |##################

###########################|*.perspective |# operating system

|*.perspectivev3 |##################

/bin/* |*.mode1v3 |

!/bin/data/ |*.mode2v3 |# Linux

|# XCode 4 |*~

######### |xcuserdata |# KDE

# general |*.xcworkspace |.directory

######### | |.AppleDouble

|# Code::Blocks |

[Bb]uild/ |*.depend |# OSX

[Oo]bj/ |*.layout |.DS_Store

*.o | |*.swp

[Dd]ebug*/ |# Visual Studio |*~.nib

[Rr]elease*/ |*.sdf |# Thumbnails

*.mode* |*.opensdf |._*

*.app/ |*.suo |

*.pyc |*.pdb |# Windows

.svn/ |*.ilk |# Image file caches

*.log |*.aps |Thumbs.db

|ipch/ |# Folder config file

######################## | |Desktop.ini

# IDE files which should |# Eclipse |

# be ignored |.metadata |# Android

######################## |local.properties |.csettingsThis might look like magic to you, but let us just continue for now, you can always look up more information on the .gitignore syntax later, for example here.

git status

A command which we will use very often is git status. This command enables us to see the current state of a repository at a glance. It offers some flags to fine-tune its output (like most Git commands).

Alright, let's use git status -u to see what's going on in our repository. The -u flag makes sure we see all untracked files, even in subdirectories:

$ git status -u

# On branch master

#

# Initial commit

#

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

#

# .gitignore

# Makefile

# addons.make

# bin/data/.gitkeep

# config.make

# demoProject.cbp

# demoProject.workspace

# src/main.cpp

# src/ofApp.cpp

# src/ofApp.h

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)The output tells us which branch we are currently on (master), that we haven't committed anything yet, and that there are a couple of untracked files (i.e. not yet known to Git) in the repository and, importantly, what we should do next. Using git status -s is an option to get more condensed output.

The list of files looks correct, so far so good! You might have noticed the .gitkeep file in bin/data/. Git only tracks files, not directories, which means that empty directories are not visible to Git. A common technique to work around this, if you want to have empty directories (e.g. for future output files) in your repository, is to place an empty file there, which makes sure that that directory can be added to Git. Naming that file .gitkeep is just a convention, and has no special meaning to Git.

If we compile the OF project now, some additional files will be created in the /bin folder. Because we added a .gitignore file in the previous step, these files will not be picked up by Git. We can check this by running git status -u again.

git add

The next step is to stage the untracked files using git add. This will put those files into the index, as discussed previously.

We stage untracked files and modifications to files already in the repository with the command git add <filespec>, where <filespec> describes one or more files or directories, so could be for example addons.make, src or *.cpp.

We can also add all files and modifications in the repository with git add ., but as this is a catch-all filespec, we will have to check the output of git status -u first, to make sure no unwanted files are missed by the .gitignore pattern and would slip into the repository! Since we just made sure our git status looks alright, let's do it:

$ git add .You will notice a change when we run git status next:

$ git status

# On branch master

#

# Initial commit

#

# Changes to be committed:

# (use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

#

# new file: .gitignore

# new file: Makefile

# new file: addons.make

# new file: bin/data/.gitkeep

# new file: config.make

# new file: demoProject.cbp

# new file: demoProject.workspace

# new file: src/main.cpp

# new file: src/ofApp.cpp

# new file: src/ofApp.h

#All those untracked files are now in the "Changes to be committed" section, and so will end up in the next commit we make (if we don't unstage them before that).

To unstage changes we have accidentally staged, we use git rm --cached <file> (for newly added files) or git reset HEAD <file> (for modified files). As usual, git status reminds us of these commands where appropriate.

git commit

Now that we've prepared the staging area/index for our first commit, we can go ahead and do it. To this end we will use git commit. We can supply a required commit message at the same time by using the -m flag, otherwise Git will open an editor where we can enter a message (and then save and exit to proceed).

$ git commit -m "Add initial set of files."

[master (root-commit) 3ef08e9] Add initial set of files.

10 files changed, 388 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 .gitignore

create mode 100644 Makefile

create mode 100644 addons.make

create mode 100644 bin/data/.gitkeep

create mode 100644 config.make

create mode 100644 demoProject.cbp

create mode 100644 demoProject.workspace

create mode 100644 src/main.cpp

create mode 100644 src/ofApp.cpp

create mode 100644 src/ofApp.hThe first line of the output shows us the branch we are on (master), and that this was our first commit, creating the root of our commit tree. Also, we see the hash (i.e. the unique ID) of the commit we just created (3ef08e9) and the commit message. The hash is given in a short form, as it's often sufficient to only supply the first seven or so characters of the hash to uniquely identify a commit (Git will complain if that's not the case). The next line roughly describes the changes that were committed, how many files were changed and how many insertions and deletions were committed. The rest lists the files new to Git, the mysterious mode 100644 is a unix-style description of the file permissions, 100644 is a regular, non-executable file (100755 would be an executable file).

Now, let's check our status to see what's going on in the repository:

$ git status

# On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory cleanHooray, that's the all-clear, all systems green message! It means that the working directory as it is right now is already committed to Git (with the exception of ignored files). It's often a good idea, whenever you start or stop working in a repository, to start from this state, as you will always be able to fall back to this point if things go wrong.

Now that we have made our initial commit, we can make our first customizations to the OF project. Onwards!

First edits

OK, we have a clean slate now, so let's start playing around with our OF project. A programming tutorial wouldn't be complete without saying hello to the world, so let's do that: Open ofApp.cpp, and in the implementation of void ofApp::setup(), add an appropriate message, e.g. cout << "Hello world";, and save the file.

We have just made a modification to a file that Git is tracking, so it should pick up on this, right? Let's check, using git status (you hopefully already guessed that part):

$ git status

# On branch master

# Changes not staged for commit:

# (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

# (use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

#

# modified: src/ofApp.cpp

#

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Alright, Git tells us it knows that we modified ofApp.cpp. Note that now the entry is in a section called "Changes not staged for commit", not "untracked files" as before. Again, git status offers instructions for what we could want to do next, very convenient.

git diff

Now, let's find out what exactly we changed in ofApp.cpp. For this, git diff is used. It can be used to compare states between all kinds of areas (check out the examples section of the man page), but in its simplest form, git diff, allows us to view the changes we made relative to the index (staging area for the next commit). In other words, the differences are what we could tell Git to further add to the index but we still haven't." (from the man page). (Use the --staged option to see the diff of already staged changes.) Let's check it out:

$ git diff

diff --git a/src/ofApp.cpp b/src/ofApp.cpp

index b182cce..8018cf7 100644

--- a/src/ofApp.cpp

+++ b/src/ofApp.cpp

@@ -3,6 +3,7 @@

//--------------------------------------------------------------

void ofApp::setup(){

+ cout << "Hello world!";

}

//--------------------------------------------------------------This output shows the difference between two files in the unified diff format (diff is a popular Unix tool for comparing text files). It looks pretty confusing, but let's pick it apart a bit to highlight the most useful parts.

The first line denotes the two different files being compared, denoted as a/... and b/.... If we have not just renamed a file, those two will typically be identical.

The next couple of lines further define what exactly is being compared, but that's not interesting to us until we come to the line starting with @@. This defines a so-called "hunk", which means it tells us what part of the file is being shown next. In the original state (prefixed by -), this section starts at line 3, and goes on for 6 lines. In the new state (prefix +), the section starts at line 3, and goes on for 7 lines.

Next, we see the actual changes, with a couple of lines around it for context. Unchanged lines start with a space, added lines with a +, and removed lines with a -. A modified line will show up as a removed line, followed by an added line. We can see that one line containing a hello world message was added.

Now that we have made some changes, we can compile and run the program to confirm it works as expected, and we didn't make a mistake. Then, we can prepare a commit with the modification, as before:

$ git add src/ofApp.cpp

$ git status

# On branch master

# Changes to be committed:

# (use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

#

# modified: src/ofApp.cpp

#Before we commit again, a couple of words regarding commits and commit messages:

First, a good mantra to remember is to "commit early, commit often". This means you should create frequent small commits, whenever a somewhat self-contained element of code is finished (e.g. implementing a new function, fixing a small bug, refactoring something) as opposed to whole features (e.g. "Implement optical flow tracking for my installation.") or mixing different changes together ("Updated Readme, increased performance, removed unused Kinect interaction.") . The reasoning behind this is that it creates a fine-grained trail of changes, so when something breaks, it is easier to find out which (small) change caused the problem (e.g. with tools like git bisect), and fix it.

Second, write good commit messages. This will make it easier for everybody else, and future you in a couple of months, to figure out what some commit does. A good, concise convention for how a good commit message looks can be found here. In short, you should have a short (about 50 characters or less), capitalized, imperative summary (e.g. "Fix bug in the file saving function"). If this is not enough, follow this with a blank line(!) and a more detailed summary, wrapping lines to about 72 characters. (If your terminal supports this, omitting the second quotation mark allows you to enter multiple lines. Otherwise, omit the -m flag to compose the commit message in the editor.)

Now that that is out of the way, we can commit the change we just added, and check the status afterwards:

$ git commit -m "Add welcome message"

[master e84ba14] Add welcome message

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

$ git status

# On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory cleanBranches and merging

Branches and merging are the bread and butter of Git, so you will be branching and merging a lot. Branching and merging often is a workflow encouraged by Git, as those are computationally cheap operations. We are getting into some slightly more-advanced stuff, so if you don't quite grasp it right away don't be worried.

For example, if we want to create some new feature, or fix a bug in our program, it is prudent to start this work on a branch separated from the main branch. This has several advantages:

- Our work on is contained in this branch.

- We can quickly and easily switch to another topic of work if needed.

- The main branch is unaffected by our work as long as it's not merged, so normal operations can continue in the meantime (e.g. when we create an experimental addition to an OF addon other people are using).

git branch and git checkout

To get a list of the branches in a repository, we use git branch without arguments (* denotes the current branch). Since we only have one branch for now, this is not very exciting:

$ git branch

* masterTo create a new branch, we use git branch <branchname>. To then check out that branch, to make it the current one, we use git checkout <branchname>. There is a shorter way to achieve both operations in one, using git checkout -b <branchname>, so let's use that to create and check out a new branch called celebration:

$ git checkout -b celebration

Switched to a new branch 'celebration'

$ git branch

* celebration

masterTo celebrate, let's add a second message after the "Hello World", e.g. cout << "Yeah, it works";. Let's confirm that Git has picked this up, using git diff as before:

$ git diff

diff --git a/src/ofApp.cpp b/src/ofApp.cpp

index 8018cf7..59d84fa 100644

--- a/src/ofApp.cpp

+++ b/src/ofApp.cpp

@@ -4,6 +4,7 @@

void ofApp::setup(){

cout << "Hello world!";

+ cout << "\nYeah, it works!";

}

//--------------------------------------------------------------If we run git status again, it will show that we are on the celebration branch now:

$ git status

# On branch celebration

# Changes not staged for commit:

# (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

# (use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

#

# modified: src/ofApp.cpp

#

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Because we have confirmed that the list of changes to be staged and committed is alright, we can take a little shortcut. Using the -a flag of git commit, we can tell Git to automatically stage modified or deleted files (new files are not affected) when committing, so we can skip the git add step:

$ git commit -am "Let us celebrate!"

[celebration bc636f4] Let us celebrate!

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

$ git status

# On branch celebration

nothing to commit, working directory cleanMerging branches

Let us meanwhile add a feature on the master branch. First, we check out the master branch:

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'Now, we can add some code to switch the background color if the space key is pressed. You should be able to recognize what I did by looking at the output of git diff. Try to approximately replicate these changes:

$ git diff

diff --git a/src/ofApp.cpp b/src/ofApp.cpp

index 8018cf7..f7e3dbc 100644

--- a/src/ofApp.cpp

+++ b/src/ofApp.cpp

@@ -18,12 +18,16 @@ void ofApp::draw(){

//--------------------------------------------------------------

void ofApp::keyPressed(int key){

-

+ if (key == ' ') {

+ ofBackground(255);

+ }

}

//--------------------------------------------------------------

void ofApp::keyReleased(int key){

-

+ if (key == ' ') {

+ ofBackground(127);

+ }

}

//--------------------------------------------------------------Next, we again commit quickly (as we already checked the modifications to be committed with git diff):

$ git commit -am "Add background switching"

[master 7cc405c] Add background switching

1 file changed, 6 insertions(+), 2 deletions(-)git log

To show commit logs, we can use the git log command. In it's default form, git log shows a plain list of commits, printing their hashes, timestamp, author and commit message. Its output is heavily customizable, and one nice thing we can do is generate a primitive tree view with this incantation (which you could save under an alias to make it shorter, but this is out of scope for this tutorial):

$ git log --all --graph --decorate --oneline

* bc636f4 (celebration) Let us celebrate!

| * 7cc405c (HEAD, master) Add background switching

|/

* e84ba14 Add welcome message

* 3ef08e9 Add initial set of files.We see the whole history of the repository here, showing the branch structure, including brief commit messages. We can also see the branch tips in parentheses, and also the current branch (where HEAD points to). We realize that the "Let us celebrate" commit is not yet included in master, so let's do that now!

git merge

We can now merge the celebration branch back into our master branch to make our celebratory message available there too. This happens with the git merge command. We use git merge <branchname> to merge another branch into the current branch, like so:

$ git merge celebration

Auto-merging src/ofApp.cpp

Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

src/ofApp.cpp | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)Git automatically figured out how to merge ofApp.cpp so that master now contains the modifications from both branches (go ahead and take a look at ofApp.cpp now).

The tree view now looks like this:

$ git log --all --graph --decorate --oneline

* 1c6d4aa (HEAD, master) Merge branch 'celebration'

|\

| * bc636f4 (celebration) Let us celebrate!

* | 7cc405c Add background switching

|/

* e84ba14 Add welcome message

* 3ef08e9 Add initial set of files.We can see that the two branches have been merged together successfully, so master now contains all our modifications. Also note that the celebration branch is unaffected by the merge, it's still pointing to its original commit.

Next, we shall find out what happens if merging does not go so smoothly.

git reset

First, purely for demonstration purposes, we use git reset to undo the merge commit we just made. This can be a dangerous command, because we can erase commits with it, so we have to be careful. It's always useful to do a git status immediately before git reset, just to make sure the repository is in the state we think it is. git reset --hard HEAD~<N> sets the current branch back by <N> commits, discarding the rest of the commits in the process if they are not part of another branch. They can still be recovered using git reflog, but that's a bit too complicated to show here. Generally, it's hard to really lose things you have previously committed, so if you accidentally deleted some important history, don't despair immediately. :-)

In contrast, the --soft flag just moves the HEAD pointer to another commit, but leaves our working directory and index unchanged. This can be useful e.g. for undoing commits.

Anyway, let's reset our master branch back one commit now:

$ git reset --hard HEAD~1

HEAD is now at 68d2674 Add background switchingYou can consult the tree view again to see that the merge commit has disappeared, and master is back at "Add background switching". Now, let's try to make a merge fail.

Merge conflicts

Git is pretty smart when merging branches together, but sometimes (typically when the same line of code was edited differently in both branches) it does not know how to merge properly, which will result in a merge conflict. It's up to us to resolve a merge conflict manually.

Now, let's create a commit which will create a conflict. We just add a second output line after the "Hello world" statement. Since in the celebration branch, another statement was also added right after "Hello world", Git will not know how to correctly resolve this. Our cout statement looks like this:

$ git diff

diff --git a/src/ofApp.cpp b/src/ofApp.cpp

index f7e3dbc..6e232ba 100644

--- a/src/ofApp.cpp

+++ b/src/ofApp.cpp

@@ -4,6 +4,7 @@

void ofApp::setup(){

cout << "Hello world!";

+ cout << "\nThis is not going to end well!";

}

//--------------------------------------------------------------Now we will create a commit (we are still on master):

$ git commit -am "Trigger a conflict"

[master 2608b52] Trigger a conflict

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)When we attempt to merge celebration into master, bad things happen:

$ git merge celebration

Auto-merging src/ofApp.cpp

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in src/ofApp.cpp

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.When a conflict is detected by Git, it will stop the merging process and put "conflict markers" into the conflicted files. Those markers look like this:

$ head -n 14 src/ofApp.cpp

#include "ofApp.h"

//--------------------------------------------------------------

void ofApp::setup(){

cout << "Hello world!";

<<<<<<< HEAD

cout << "\nThis is not going to end well!";

=======

cout << "\nYeah, it works!";

>>>>>>> celebration

}

//--------------------------------------------------------------The part between <<< and === shows the file as it is in HEAD, the current branch we want to merge into. The part between === and >>> shows the file as it is in the named branch, in our case celebration. What we have to do now next is resolve the conflict by implementing the conflicted section in a way which makes sense for our program, remove the conflict markers and save the file. For example, we can make the conflicted section look like this:

void ofApp::setup(){

cout << "Conflict averted!";

cout << "\nHello world!";

cout << "\nYeah, it works!";

}After doing this, Git still knows that there has been a conflict, and git status again tells us what to do next:

$ git status

# On branch master

# You have unmerged paths.

# (fix conflicts and run "git commit")

#

# Unmerged paths:

# (use "git add <file>..." to mark resolution)

#

# both modified: src/ofApp.cpp

#

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Obediently, we run git add src/ofApp.cpp to stage our conflict-free file and mark the conflict as resolved. Now, we can finish the merge. If we omit the -m <message> part, git commit will open an editor (which one depends on your setup) with a proposed commit message which mentions the files for which conflicts had occured. You can either try that way, or just create a self-made commit message directly, as usual:

$ git commit -m "Merge after resolving conflict"

[master 29d152e] Merge after resolving conflictAll that remains is to check if everything worked alright, and take a last look at our tree view:

$ git status

# On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

$ git log --all --graph --decorate --oneline

* 29d152e (HEAD, master) Merge after resolving conflict

|\

| * d9be50b (celebration) Let us celebrate!

* | 2608b52 Trigger a conflict

* | e822ea4 Add background switching

|/

* 1964a43 Add welcome message

* f6caa7b Add initial set of files.Congratulations, you have just resolved your first merge conflict! This concludes the walk-through portion of this chapter, I will continue with more high-level explanations of Git features.

git tag

During your work, you will encounter special commits, which mark significant stations in your project's history, for example released versions, or the state of your code when it was installed somewhere, or handed off to your customer. You can do this easily with Git tags. Use git tag somename to put a tag on the current commit. This tag now permanently points to that commit, and you can (mostly) use it in Git commands just like commit hashes and branch names. For example, git checkout v1.2 will check out the repository's state (if the tag exists) just like it was when you published version 1.2.

Remote repositories and Github

An important aspect of your work may involve collaboration with others. With Git, this typically involves one or more remote repositories (short remotes), to which you push your modifications, and from which you fetch the modifications of others.

One of several popular hosting platforms for Git repositories is Github. Github offers repository hosting (public and private), project wiki pages, an issue tracker, social features, project web pages, etc. OpenFrameworks primarily uses Github to host its source code repositories and the openFrameworks issue tracker.

Delving deeper into Github's features would lead too far here, so I'll just outline the typical operations you will deal with when interacting with Github repositories.

Setting up and remotes

To start a project on Github, you have several options:

- If you want to have your own copy of the source code of a project that already lives online, you fork that repository, including all history, ending up with a copy of it under your account.

- If you want to start a fresh project, you can create a new repository. Github will display instructions for creating an empty local repository, or for connecting the new repository to an existing local one.

If there's already a Git repository online somewhere, you can also clone that repository to get a copy of it on your local machine. This command is not limited to Github repositories, but can be used with all Git repositories, see the git clone docs for what you can do with git clone.

The remote repositories are added as so-called remotes to your local repository's configuration (either automatically, or using git remote add). Think about it as a target identifier you supply to Git commands if you want to work with remote repositories. A remote is just an identifier that points to the Github (or other) URL where that repository lives.

It is customary that a "parent" repository (i.e. the repository under your Github account) is called origin, and a repository you forked from is called upstream. You can get the list of current remotes using git remote (add -v to see more info).

Fetching and pulling

Now that you have a remote repository configured, you can interact with it via git push and git fetch. As the names imply, git fetch fetches branches from a remote, so to get the latest version of the master branch of your Github repo, you'd do git fetch origin master (the syntax is git fetch <remote> <branchName>). If you wanted to obtain the newest modifications from your upstream remote, instead, you'd do git fetch upstream master. After this has finished, you'll have an additional branch called origin/master in your repository. You can check this with git branch -a - remote branches are listed with a remotes/ prefix.

To integrate the newest changes of this remote branch into your local master, you first do git checkout master, to be sure you're on the correct branch. Then, you should make sure that the state of the repository is in order, using git status. Next, you merge the remote branch, just like any other branch, using git merge origin/master. If all went well, you now have all the latest changes integrated into your master branch. If not, you'll probably have to fix some conflicts, as you already learned above.

A commonly used shortcut for the subsequent operations git fetch and git merge is git pull - you can use that instead if you like. Personally, I tend to use fetch and merge separately, as it gives you a bit more control over what happens.

Pushing

When you have commits or branches you want to share with others, you will push them onto your remote repository (e.g. on Github) using git push, for example with git push origin awesome-feature. If the branch does not exist yet, it gets created in the remote repository, else it gets updated. Others can then fetch the new branch from your remote repository to integrate into their repositories. Note that Git tags are only pushed to a remote if you supply the --tags flag.

Pull requests

A central feature of the Gitub collaboration model are pull requests. Pull requests (or "PRs" for short) are ways to get your personal changes integrated into a repository you forked (it's important that you forked the repository into your own account instead of getting a copy by other means).

Let's walk through this with an example: Say you found a bug in openFrameworks, and want to fix it. You have already forked openFrameworks to your account, created a local copy, and created a branch from master, called fix-uglybug, following our contribution guidelines (ideally there's a bug report first where we discuss the proper way to fix the bug, but let's leave that part aside for now). To get the openFrameworks developers to review (and hopefully integrate) your bugfix, you push your branch to your remote (git push origin fix-uglybug), then switch to the freshly uploaded branch in the Github web interface, and click the green "compare, review, create a pull request" button. Following the instructions, you will be able to compare your branch to the target branch (typically openFrameworks' master branch), review the changes you made, type up a description of the pull request, and send it.

A pull request enables an easy review of your changes and offers a discussion platform where the changes can be discussed, updated, and finally merged with one click, incorporating your changes into the upstream repository.

Popular GUI clients

While working with the console commands offers the whole power of Git, it is sometimes more convenient to do at least part of the version control work in an application with a GUI. There are a couple of GUI applications available (depending on platform), and which one you use is often a matter of taste (and functionality of the individual programs), so I will just enumerate a couple of popular candidates. There's also a curated list of applications here, and a pretty exhaustive list here.

- git-gui and gitk are simple interfaces distributed with Git.

- Github offers clients for Windows and Mac which also offer integration with Github (not only Git).

- Gitg is an open-source Git GUI for Linux.

- Tower is a Git GUI for Mac.

- GitExtensions is an open-source Git GUI for Windows.

- smartGit runs on Windows, Mac, Linux.

You should try a few of the options and use what you like best. Personally, I use a combination of console commands and Gitg on Linux. I use the GUI mainly for branch navigation, selecting and staging modifications, and committing, and the command line interface for working with remotes and more complicated operations.

Conclusion

Tips & tricks

This section contains a loose collection of tips and tricks around avoiding common pitfalls and working with Git:

- Collaborating with users using different operating systems can be tricky because MacOS/Linux and Windows use different characters to indicate a new line in files (

\nand\r\n, respectively). You can configure Git according to existing guidelines to avoid most problems. - Some editors automatically remove trailing whitespace in files when saving. This can lead to commits containing unintentional modifications, which can make browsing a file's change history more confusing. Most relevant Git commands (e.g.

git diff) accept the-wflag to ignore whitespace changes. - When you realize that you want to add some more changes to your last commit, you can use the

--amendflag when committing to add your staged changes to the last commit and adjust the commit message. This rewrites that commit, so only do that if you haven't pushed your commit yet! - When you want to stage only part of the modifications in a file, you can use

git add -p <file>. This switches to an interactive view where you can decide whether or not to add each change chunk. - Git can be told to colorize the terminal output, which is pretty helpful.

- Use

git rmandgit mvwhen removing or moving files, respectively. If you don't, the index does not get properly updated. You can rungit add -uto update the index manually.

Further reading

Now we are at the end of this quick introduction to Git, and while I have covered the most important things you need to know to get you up and running, I have only touched the surface of what Git can do.

Probably the most important thing left now is to point out where you can learn more about Git, and where you can turn to when things don't work out as expected:

- Learning resources:

- GitRef is an awesome short primer on Git fundamentals.

- The Git home page is probably the most unified but comprehensive online resource. Among others, it hosts:

- The free ProGit book, readable online. Awesome to get in-depth information about all things Git.

- The Git reference, which has the documentation about all Git commands, their options and usage.

- Try Git is an excellent interactive tutorial.

- Github offers a Hello World introduction to Git and Github.

- There are some websites available which visualize/animate the workings of Git, see here, here or here.

- Gitignore patterns for a lot of different situations can be found e.g. here or at gitignore.io.

- Get help:

- Google the errors you get!

- Stack Overflow is an awesome resources to find answers to problems you encounter (probably someone had the same problem before), and to ask questions yourself! There's even a separate tag for Git.

- If you're not successful with Stackoverflow, the openFrameworks forum has a separate category called "revision control" for questions around this topic.

Finally, I hope that this chapter made you realize how useful it can be to integrate version control into your creative coding workflow, and that you will one day soon look fondly back on the days of zip files called Awesome_project_really_final.zip.